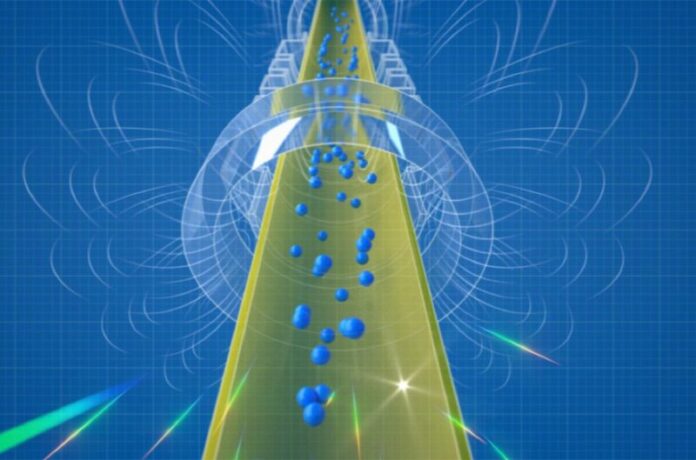

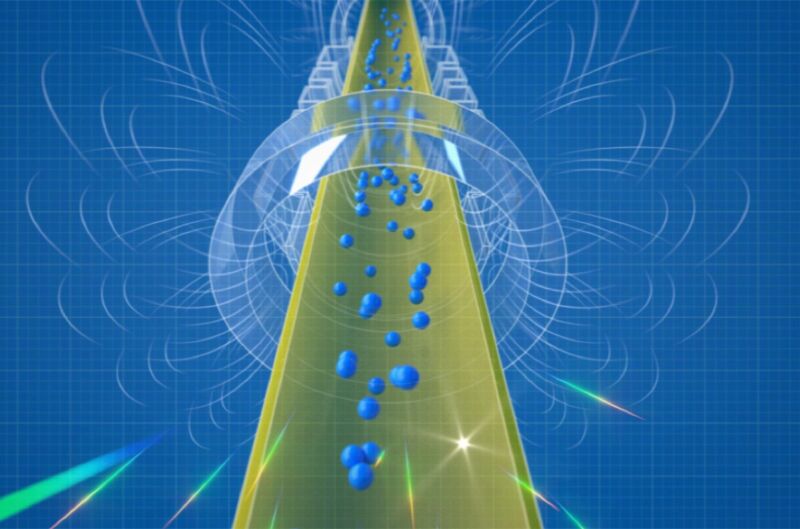

Enlarge / An artist's conceptual rendering of antihydrogen atoms falling out the bottom of the magnetic trap of the ALPHA-g apparatus. (credit: Keyi )

CERN physicists have shown that antimatter falls downward due to gravity, just like regular matter, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature. It's not a particularly surprising result—it would have been huge news had antimatter been found to be repulsed by gravity and "fall" upward—but it does tell us a bit but more about antimatter and brings physicists one step closer to resolving one of the most elusive mysteries surrounding the earliest moments of our universe.

As the name implies, antimatter is the exact opposite of ordinary matter, as it is made of antiparticles instead of ordinary particles. These antiparticles are identical in mass to their regular counterparts. But just like looking in a mirror reverses left and right, the electrical charges of antiparticles are reversed. So an anti-electron would have a positive instead of a negative charge while an antiproton would have a negative instead of a positive charge. When antimatter meets matter, both particles are annihilated and their combined masses are converted into pure energy. (It's what fuels the fictional USS Enterprise, as any Star Trek fan can tell you.)

As far as we know, antimatter doesn’t exist naturally in the known universe, although we can now create small amounts at places like CERN's Antimatter Factory. But scientists believe that ten billionths of a second after the Big Bang, there was an abundance of antimatter. The nascent universe was incredibly hot and infinitely dense, so much so that energy and mass were virtually interchangeable. New particles and antiparticles were constantly being created and hurling themselves, kamikaze-like, at their nearest polar opposites, thereby annihilating both matter and antimatter back into energy in a great cosmic war of attrition.

Read 7 remaining paragraphs | Comments

Ars Technica - All contentContinue reading/original-link]