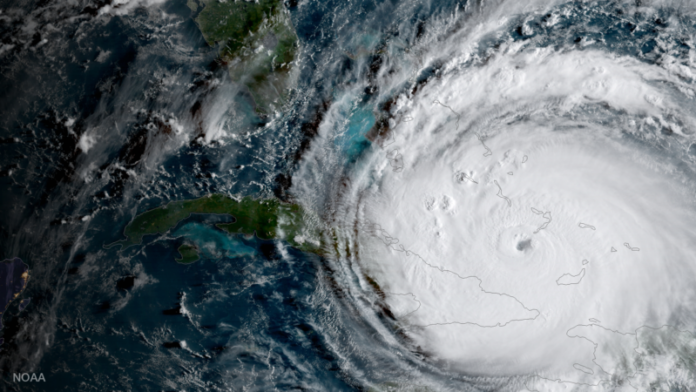

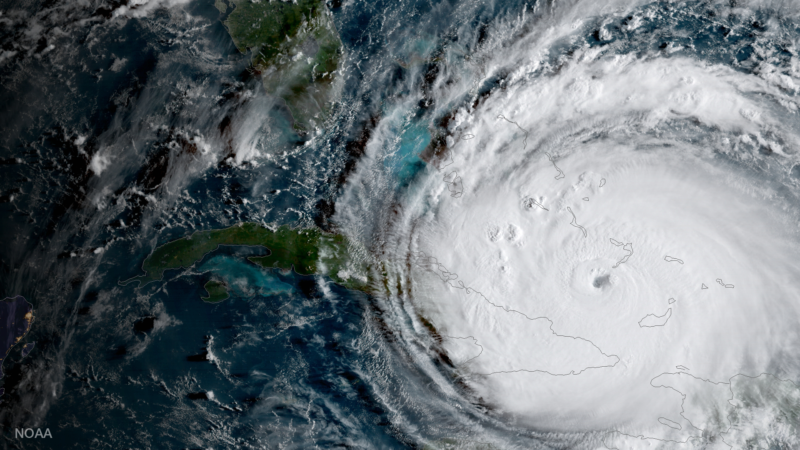

Enlarge / Hurricane Irma as seen by satellite in 2019. (credit: NOAA)

Hurricane Lee wasn’t bothering anyone in early September, churning far out at sea somewhere between Africa and North America. A wall of high pressure stood in its westward path, poised to deflect the storm away from Florida and in a grand arc northeast. Heading where, exactly? It was 10 days out from the earliest possible landfall—eons in weather forecasting—but meteorologists at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, or ECMWF, were watching closely. The tiniest uncertainties could make the difference between a rainy day in Scotland or serious trouble for the US Northeast.

Typically, weather forecasters would rely on models of atmospheric physics to make that call. This time, they had another tool: a new generation of AI-based weather models developed by chipmaker Nvidia, Chinese tech giant Huawei, and Google’s AI unit DeepMind. For Lee, the three tech-company models predicted a path that would strike somewhere between Rhode Island and Nova Scotia—forecasts that generally agreed with the official physics-based outlook. Land-ho, somewhere. The devil, of course, was in the details.

Weather forecasters describe the arrival of AI models with language that seems out of place in their forward-looking profession: “Sudden.” “Unexpected.” “It seemed to just come out of nowhere,” says Mark DeMaria, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University who recently retired from leading a division of the US National Hurricane Center. When he started a project this year with the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration to validate Nvidia’s FourCastNet model against real-time storm data, he was a “skeptic” of the new models, he says. “I thought there was no chance that it could work.”

Read 13 remaining paragraphs | Comments

Ars Technica - All contentContinue reading/original-link]