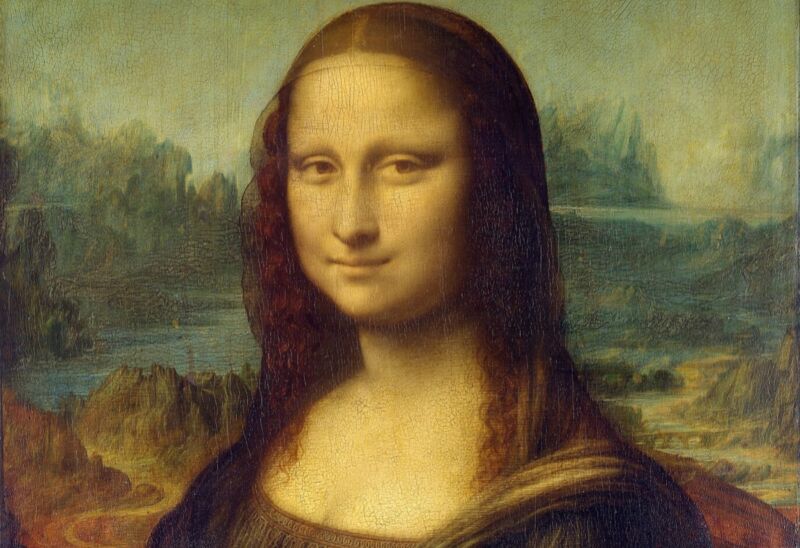

Enlarge / A tiny fleck of paint, taken from the Mona Lisa, is revealing insights into previously unknown steps of Leonardo da Vinci's process. (credit: Public domain)

When Leonardo da Vinci was creating his masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, he may have experimented with lead oxide in his base layer, resulting in trace amounts of a compound called plumbonacrite. It forms when lead oxides combine with oil, a common mixture to help paint dry, used by later artists like Rembrandt. But the presence of plumbonacrite in the Mona Lisa is the first time the compound has been detected in an Italian Renaissance painting, suggesting that da Vinci could have pioneered this technique, according to the authors of a recent paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Fewer than 20 of da Vinci's paintings have survived, and the Mona Lisa is by far the most famous, inspiring a 1950s hit song by Nat King Cole and featuring prominently in last year's Glass Onion: a Knives Out Mystery, among other pop culture mentions. The painting is in remarkably good condition given its age, but art conservationists and da Vinci scholars alike are eager to learn as much as possible about the materials the Renaissance master used to create his works.

There have been some recent scientific investigations of da Vinci's works, which revealed that he varied the materials used for his paintings, especially concerning the ground layers applied between the wooden panel surface and the subsequent paint layers. For instance, for his Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1503–1519), he used a typical Italian Renaissance gesso for the ground layer, followed by a lead white priming layer. But for La Belle Ferronniere (c. 1495–1497), da Vinci used an oil-based ground layer made of white and red lead.

Read 10 remaining paragraphs | Comments

Ars Technica - All contentContinue reading/original-link]