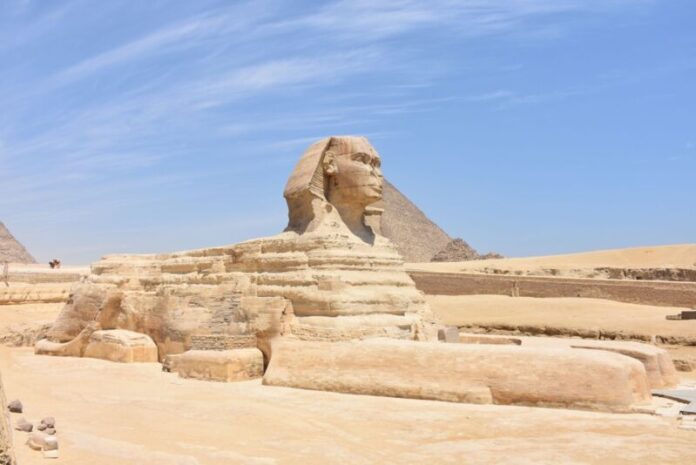

Enlarge / Experiments yield fresh evidence to support controversial hypothesis about the formation of the Great Sphinx of Giza. (credit: MusikAnimal/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Leif Ristroph, a physicist and applied mathematician at New York University, was conducting experiments on how clay erodes in response to flowing water when he noticed tiny shapes emerging that resembled seated lions—in essence, miniature versions of the Great Sphinx of Giza in Egypt. Further experiments provided evidence in support of a longstanding hypothesis that natural processes first created a land formation known as a yardang, after which humans added additional details to create the final statue. Initial results were first presented last year as part of the American Physical Society's Gallery of Fluid Motion, with a full paper being published this week in the journal Physical Review Fluids.

"Our results suggest that Sphinx-like structures can form under fairly commonplace conditions," Ristroph et al. wrote in their paper. "These findings hardly resolve the mysteries behind yardangs and the Great Sphinx, but perhaps they provoke us to wonder what awe-inspiring landforms ancient people could have encountered in the deserts of Egypt and why they might have envisioned a fantastic creature."

In 2018, Ristroph's applied mathematics lab fine-tuned the recipe for blowing the perfect bubble based on experiments with soapy thin films, pinpointing exactly what wind speed is needed to push out the film and cause it to form a bubble, and how that speed depends on parameters like the size of the wand. (You want a circular wand with a 1.5-inch perimeter, and you should gently blow at a consistent 6.9 cm/s.)

Read 10 remaining paragraphs | Comments

Ars Technica - All contentContinue reading/original-link]