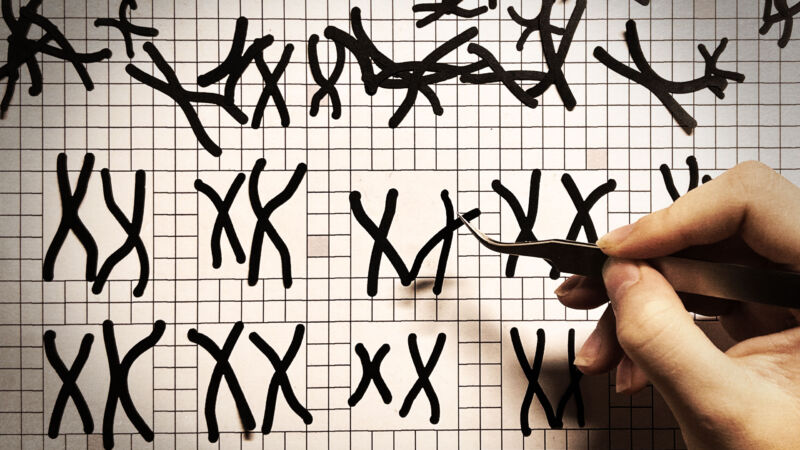

Enlarge (credit: Aurich Lawson)

In 1972, Janet Rowley sat at her dining room table and cut tiny chromosomes from photographs she had taken in her laboratory. One by one, she snipped out the small figures her children teasingly called paper dolls. She then carefully laid them out in 23 matching pairs—and warned her kids not to sneeze.

The physician-scientist had just mastered a new chromosome staining technique in a year-long sabbatical at Oxford. But it was in the dining room of her Chicago home where she made the discovery that would dramatically alter the course of cancer research.

Read 29 remaining paragraphs | Comments

Ars Technica - All contentContinue reading/original-link]